I love railways! Or, to put it another way, I am an enthusiastic ferroequinologist. A gricer. An explorer of all things train, including a builder of model railways. Travelling by rail is my primary choice when I can, but it is also a source of leisure for me. In this time of introspection and recouperation that is my sabbatical, I have recently felt it would be interesting to examine this love of mine.

Yesterday I had a very pleasant day chugging along the heritage Spa Valley Railway on the Kent/Sussex border. Why did I jump on a train at seven in the morning, travel for two-and-a-bit hours in rush hour via one of London’s busiest stations, only to get on another train and ride up and down a valley four times, before jumping back on yet another train at the other end to eventually get home about eight in the evening? And why did I enjoy basically every minute of it? You could say, in honour of the little tank engine that pulled my train at times along that picturesque valley, I was chuffed with my day!

As I sat in a 1950s designed buffet coach, sipping a glass of the local Kent cider and enjoying views of the High Weald “area of outstanding natural beauty”, with its fallow deer in the woods and fields, and primroses on the verge, it crossed my mind that this was an idealised view of what is known as the romanticism of railways. That is the joy of travelling at twenty-five miles per hour behind a little steam engine. Listening to it clank, hiss, puff, simmer and whistle. And enjoy plumes of smoke, cinders and steam that carry the soft sulphuric smell of burning coal through open carriage windows.

You arrive at restored stations with their elegant Victorian iron work, wooden signal boxes and inviting scone filled tea rooms. Enthusiastic volunteers in black three-piece uniforms and flat caps greet you whilst checking pocket watches and blowing on silver whistles. Everyone is “playing trains” with the enthusiasm of children in books by the Reverend W. Awdry or Edith Nesbit. Alongside the line and from the train, strangers wave back and forth at each other, often led by the soot covered driver and fireman in their blue overalls and flat caps. Although, as the aforementioned Rev. Awdry reminds us, the engines know that the children are actually waving at them!

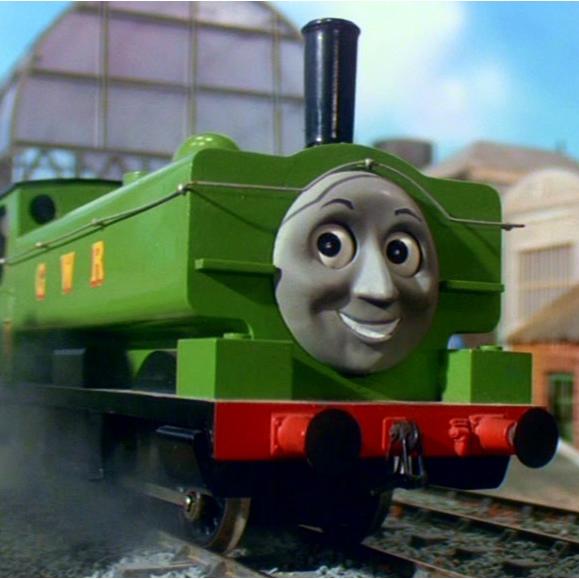

It is almost impossible to not consider the effect of the Thomas the Tank Engine railway stories on generations of children in this country, and beyond, when talking about a love of railways. My dear dad, from whom my love of railways stems, used to read those stories to me endlessly as a child while I sat in bed in my Thomas pyjamas. I had a Hornby model Thomas, Annie and Clarabel for our model railway. I would watch the TV show, listening to Ringo Starr describe the antics of engines big and small as they argued with troublesome trucks or charmed elegant coaches, whilst all the time trying to be as “useful” as possible.

Finally, there was the much-played vinyl recording of Willie Rushton reading the first stories of Duck, the Great Western Engine. I could almost quote that record verbatim, trying to mimic the west country accent Willie adopted for Duck as he rightly pointed out that there were two ways of doing things – “The Great Western way or the wrong way!”. Duck is still my favourite loco from the stories, and I uphold my dad’s love of the Great Western railway. I remember he and I at a model railway exhibition watching a 7mm scale Great Western pannier tank, just like Duck, shunt trucks in a yard for ages. We could have stood there all day. There is something about the green and brass of Brunel’s wonderful railway that is just a little special.

All this is why of course, when asked what noise a train makes, children will still say the equivalent of “choo choo” despite steam ending on British Railways in the 1960s.

Thus, back on those Southern Railway malachite green coaches yesterday, my head out of the window enjoying the breeze like a grinning spaniel with its ears flapping in the wind, I was in my element. However, beyond the romanticism of steam and the joy of seeing it’s stars like Flying Scotsman or the record breaking Mallard, there is something deeper there for me. How does that translate to the contemporary modern railway scene? Why do I, like so many, buy endless books, magazines and other media about trains? Why would I choose to spend a day, as I have many times, simply out “gricing”? That is riding a train to somewhere I have never been before or on a type of train I have never been on before, just for the fun of it? Why share the travel experience with a myriad of folk when I have the solitary comfort of my car available? Why is there a model railway being built in the back bedroom full of 1990’s diesels?

Recently, I was on a train heading into London St Pancras along the North Kent coast. It was late in the evening, we were heading into some weather and the sun was setting – firstly over the Thames estuary and then open fields. There was a moment when, despite travelling at high speed, time seemed to stop. I was completely engrossed in the beautiful colours. I managed to try to take a quick photo to capture this moment but it doesn’t summarise the full beauty of many minutes watching this horizon unfold in front of me. Of course, if I had been driving a car, I wouldn’t have been able to concentrate on this view and maybe there lies the root of at least one answer to those questions above.

The view from a train can be fascinating. There is very little comparison to anything else. A plane is too high to see the details. A car is often in a gulley or boxed in by verges and requires your dedicated concentration. However, a train journey can show you many things.

Firstly there is, as described above, the beautiful. Miles and miles of landscapes, punctuated with rivers, villages, church spires, woods and farms that simply cannot be viewed in any other way with such rapidity. Personal favourites include the Hope Valley in the Peak District whilst travelling between Sheffield and Manchester. The stark beauty of the eastern fens and the open beaches of the Northumbria Coast from the east coast mainline. The Malvern Hills and the rolling Cotswolds. I also have a fondness for the soft countryside of my home in Hertfordshire. Little copses sat on rising land above fields of crops whose colours tell the stories of the seasons. I am travelling to Scotland soon by train and cannot wait to traverse through the Highlands and Cairngorms and take in that landscape.

The beautiful must also include some of the great railway cathedrals. St Pancras, Paddington, Liverpool Lime Street and Bristol Temple Meads spring to mind. But also, the quaintness of Chesham on the Metropolitan Line and the art deco splendour of Exeter St Davids or Gants Hill tube station for example. All things being equal though, I would happily board a train at Arley in Worcestershire on the preserved Severn Valley Railway every time than pretty much anywhere else in the world.

On the flip side, this is also an opportunity to view the less picturesque but no less important environments of our towns and cities. I am often reminded of the concentric circles of secondary school geography lessons about city construction, as the railway takes you from first, the central business district of the city to the inner suburbs, the outer suburbs and then satellite towns of our major population centres. Although it never ceases to amaze me how quickly you are likely to see a sheep when leaving big cities, even London, by train!

It is almost universal across England as you leave a town or city by train that you will see Victorian buildings parallel to or leading to the railways, including a Railway Inn pub! These are contemporary to the building of the lines, and bar the aforementioned church steeples are likely the oldest buildings you will see from a train. This is often as railways were built to just outside the oldest parts of towns that contained no space for them. An unintended result though is the spectacular approaches on viaducts seen in places like Bath, Worcester and Berwick upon Tweed. Although it is difficult to beat the view from platform 1 at Blackfriars station in London as it traverses the Thames. I recommend you go and have a look.

Next come the “Metroland” style 1930s mock Tudor semis. Then the post war to 1970s housing in its cul-de-sacs and estates. Finally, will come the builds from the 1990s onwards, mixing with the great industrial estates of similar age. Any homogeneity that existed in any of these buildings during construction is instantly wiped out by the owners with colourful render, extensions and loft conversions that would have flabbergasted the original architects.

A plethora of back garden components, including the ubiquitous shed, flash by. These include everything from manicured lawns around smart conservatories to piles of household objet d’art varying from the ornate to, let’s be honest, junk! Plus, a vast selection of trampolines and climbing frames for children of all ages. The semi-rusty barbeques and patio furniture wrapped up against the winter weather hint at the great British optimism for a little bit of sun and a chance to turn off the heating! The house not far from Finsbury Park station that uses their back wall to hang banners containing various left wing political messages directed at passengers, is fairly unique in my experience, but I am always intrigued to see what the hot topic of the week is.

At track level, particularly in large towns and cities, we then come to what some consider to be the scourge of modern railways – graffiti. Now anyone who remembers the plot in Neighbours from the late 1980s with Helen Daniels and Nick Page, (yes, I had to look that name up), will be reminded that it takes talent to be a good graffiti artist and every now and again you see a piece that makes you genuinely think, “that’s quite impressive.”. Some of the logistics involved are also often mind boggling. It is also true that you can visit pretty much any historic or noteworthy place in Britain made of stone and you can find a name or drawing chipped into the stone to memorialise someone’s visit. Wait long enough and it becomes an exhibit – Roman soldiers were particularly noteworthy for this activity.

As a result, tags and other art of this type could be said to be part of a long human tradition. The main difference is that the Romans didn’t have to contend with high-speed trains or the chance to be electrocuted with a few thousand volts. It is this that made me question the individual whose work I saw recently, that had taken this risk to life and limb to write the word “ouch” in large 3D silver and blue letters on a railway cutting wall. Perhaps they were pre-emptively expressing what might happen later in the evening? Nevertheless, the great retaining walls, abutments and abandoned buildings of the early railway are sadly often hidden under more modern messages painted in colours and lettering that contrast heavily with their potential for nostalgia.

This nostalgia draws on a common component of many railway enthusiasts core enjoyment of their hobby including my own. They will often discuss, away from the trains themselves, the intrigue of infrastructure. If you watch the videos of someone like Geoff Marshall for example, much of what is discussed is the interest in how the system works. A recognition of the undertaking to build and run our rail network over nearly 200 years. A love of historical architecture and how, like at my local station of Royston, you can see many eras of railway buildings and construction as you interpret the environment around you. I always look for the Network Southeast branded bricks in the platform surface at Welwyn Garden City whenever I am there for example – branding for a service that stopped in the mid-1990s after only 10 years of operation. The appreciation for the logic of signalling, the cartography of map making, the understanding of how railways drive business, growth and regeneration, advertising artwork development, brand identity and the insight on technology development, tie into so much of what makes the railways an appealing destination for me and many others.

This is also represented in those who build model railways to a high standard beyond that of a “plug and play” train set. The opportunity to study and research a location. To interpret the history of a place such as a railway station is to understand how technology has evolved over time and how motivations have changed. A good example of this I like to look for is what has happened to the goods yard or if it had one, engine shed, and the associated sidings at each station. Railways were originally built for freight transfer as a priority over passengers. In most cases, like that at Royston, the yard is now a car park. However, it doesn’t take long to travel up and down the local lines and find goods sheds that are scrap yards, restaurants, taxi offices, art studios and for rent workspaces. Similarly, recently renovated brick-built warehouses often include features that once allowed the loading of goods onto a train in a siding below. Visit Granary Square in Kings Cross for this on a grand scale.

A close look will also show the overgrown or underused sidings of wooden sleepered track. This was once part of the intricate shunting manoeuvres of multitudes of coal trucks and produce vans that supplied our homes and local businesses long before the HGV and the motorway. A space that would have held track can be seen where clean granite grey ballast gives way to first brown then overgrown older layers covered in buddleia plants. In the great cuttings created by navvies and dynamite, you can often see the spacing for far more track than exists these days. Permanent way gang buildings lie abandoned along most lines and, if you know what you are looking for, these can instantly tell you which railway company built the lines. You can also see the empty routes destroyed by the Beeching Acts of the 1960s. The abandoned embankments covered in trees or the standalone bridges that no longer rumble under tons of railway traffic. A private home in what was once a Station Master’s house is a sought after fascination for many rail enthusiasts.

Just a little tip by the way. If you wish to explore these things, always sit on the right-hand side of a train facing the direction of travel. It is the best way to see these features as the return running rail will be next to you and gives space to take in the environment.

To conclude. This recent time of my life, my sabbatical and my hopes for the future, could potentially be analysed with the following railway metaphor. Whilst on a rail journey you experience the growing trepidation as the land rises outside the train window, higher and higher, overwhelming the view, until suddenly you disappear into the blackness of a tunnel. For an unknown period, all you can see is your own reflection and that of the people right next to you. There can be a feeling of claustrophobia and, as a result, you search for the subtle hint of the brick work and adjoining rails outside using the light of the carriage, just to try to expand against the shut in situation in which you find yourself. And then, just as suddenly, the luminosity increases, and you are treated to a burst of daylight and maybe a slight outbreath of relief as you return to the real world. As the cutting drops away, if you are very fortunate, you may find yourself on an embankment or viaduct providing clear and panoramic views of beautiful landscapes as you continue toward your destination.

I think I am just at that tunnel exit now and taking an initial breath of relief. My love of railways brings me a joy that I think will help sustain me on the next bit of the journey. As a result, I’m looking forward to my next trip already.

Leave a reply to Feeling Thin – Life moves pretty fast Cancel reply